Religion and Globalization:

African Christians in the United States

A paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, Atlanta, Georgia, August 15, 2003.

by Abolade Ezekiel Olagoke, Ph. D

Ezekiel Olagoke, was born in Nigeria. He obtained his B.A. in Political Science, Oklahoma State University, MA Communications, Wheaton College. He recently completed his Ph.D. in Religion/Social Change at the University of Denver. Email: aolagoke@du.edu

Introduction

One of the most critical aspects of what once constituted Western civilization was the Christian religion (Stark, 2003, Habermas, 2002). Despite its decline or mutation in the West, the Christian faith continues to attract non-Westerners in what Philip Jenkins called the “The Next Christendom” (Jenkins, 2002, Haynes, 1998: 164-188). In matters of faith and other forms of discourse, Africans are simultaneously receivers and adapters. The notion of a culture being imposed on another culture where the latter culture just acts like a receptacle, an uncritical conduit or some form of tabula rasa is questionable.[1] It is my thesis in this paper that for African immigrants in the United States under study, the Christian religion matters, and it matters considerably. In fact, in the face of national and personal uncertainties and existential nihilism where most have witnessed harrowing history of national and personal tragedies, religion not only matters, it also remains one of the most revolutionary aspects of human discourse. The summation of these immigrants’ experiences as they face difficult and uncertain lives in the West is reminiscent of Jurgen Habermas’ assertion when he states that,

“In an age of secularization and scienticization, religion remains a major factor in the moral education and motivation of individuals uprooted from other traditions, at the very least, in an age of accelerating homogenization and simultaneous manufacturing of difference, what sociologists of globalization have called glocalization, religions are articulated as the last refuge of unadulterated difference, the last reservoir of cultural autonomy.[2]

The Christian faith continues to grow at amazing rapidity outside the West (Gifford: 1991). For example, in Africa, in spite of political, social and economic upheavals, Christian faith has served as a bulwark for cultural defense, cultural identity and cultural transition (Bruce, 1996: 108-125). Africa’s disintegrating economic and political landscape has prompted Africans of various ethnic groups and professions to vote with their feet by emigrating to the West in search of greener pastures (Olagoke: 2002). Fleeing oppressive regimes, social and political dislocation, ethnic strives and religious persecution, African immigrants have established churches and African Christian Fellowships, which have dotted the cities, college campuses and suburbs of the United States (Olagoke, 2002). African immigrants have come with religious zeal and expectation not only to improve their lot in the United States but also to be a channel of assistance to their brethren in Africa. These immigrants have been attracted to the United States, which has liberally granted visas and permanent residency to many nationalities during the past few decades. Like other immigrants, Africans seek and search for academic and professional green pasture in the West and some simply come because of human need to emigrate to where they could find better fulfillment for themselves and their families (Arthur, 1998, Olagoke 2002).

Prior to the recent upsurge in African Christian initiated immigrant churches, the early 1980’s gave rise to increasing number of African Christian Student Fellowships on college campuses in the United States (Olagoke, 2002). These Christian Student Fellowships have provided haven for new African students in their transition both to campus life and the host communities in the United States.[3] The former members of these Student Fellowships have either returned to their native countries involved in national development or remained in the United States either belonging to the renamed African Christian Fellowships or African initiated Christian churches. One of such African initiated Christian Churches is Hands On Christian Church in Aurora, Colorado.

Hands On Christian Church

This paper addresses one such group of African immigrants churches (Hands On Christian Church) and the way members of the church have utilized the Christian faith in their transition to the civic life in the United States.[4] In the Denver Metro area alone, there are at least five different African initiated immigrant churches, namely: Hands On Christian Church, Ethiopian Baptist Christian Church, Agape Christian Center, Redeemed Christian Church, and Christ Harvest Fellowship. These churches have contributed to the ongoing American religious mosaic brought about by globalization, cultural transition accompanying global migration.[5] Hands On Christian Church is a racially and ethnically diverse congregation and it is part of a new religious landscape being created and expressed in different languages, and customs that may sometimes be at variance to what is practiced by orthodox or main line churches in the United States (Ebaugh, 1998; Warner, 1996). Furthermore, part of the mission objectives of the church is to bridge the century old gap between Africans and African Americans.[6]

Over the past three years, I have conducted my research at Hands On Christian Church (HOCC) in Aurora Colorado as a participant observer. The church is composed of members from about fourteen different nations of Africa and Latin American. These congregants emigrated from Zimbabwe, Liberia, Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, Kenya, Uganda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Cameroon, Senegal, Columbia, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, among many others. There are also white American families as well as African Americans members of the congregation. Over the past three years, I have conducted my research at Hands On Christian Church (HOCC) in Aurora Colorado as a participant observer. The church is composed of members from about fourteen different nations of Africa and Latin American. These congregants emigrated from Zimbabwe, Liberia, Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, Kenya, Uganda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Cameroon, Senegal, Columbia, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, among many others. There are also white American families as well as African Americans members of the congregation.

HOCC started initially as a home based gathering of immigrants about five years ago. It subsequently moved to a rented location at Aurora Middle School, staying there for almost two years before moving to its present rented location on Uvelda Road in Aurora. It is making determined effort to move to its own permanent church building when the present lease expires in about eighteen months. HOCC now averages about two hundred and fifty congregants with two services on Sunday. The first service is the Spanish congregation, starting at nine in the morning while the main service comprising members mostly from African countries and the United States starts at 10:30 a.m.

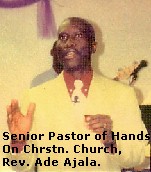

The pastor, Rev. Ade Ajala is from Nigeria and has worked in pastoral and evangelistic capacities in many parts of the world, including being part of a mission ship outreach that went to many shores of the world sharing medical needs while at the same time catering to the needs of the human spirit through evangelization of the gospel. A very amicable personality, Pastor Ade, as he is frequently called has a deep vision to bridge gaps between races with the passion and power of Jesus Christ. Reverend Ajala had his university education in Nigeria with dual degrees in Mathematics and Economics. He is the senior pastor and there are five other members of the pastoral team who help in the worship service and who are also leaders of cell groups that meet in homes in many parts of the Denver Metro area. The pastor, Rev. Ade Ajala is from Nigeria and has worked in pastoral and evangelistic capacities in many parts of the world, including being part of a mission ship outreach that went to many shores of the world sharing medical needs while at the same time catering to the needs of the human spirit through evangelization of the gospel. A very amicable personality, Pastor Ade, as he is frequently called has a deep vision to bridge gaps between races with the passion and power of Jesus Christ. Reverend Ajala had his university education in Nigeria with dual degrees in Mathematics and Economics. He is the senior pastor and there are five other members of the pastoral team who help in the worship service and who are also leaders of cell groups that meet in homes in many parts of the Denver Metro area.

Apart from the cell groups, church membership is further divided into four main “spiritual households”: 1) the house of Jeremiah; 2) the house of Benaiah, 3) the house of Nehemiah and 4) the house of Joseph. This breakdown is to enable better interaction and relationship among the members. Every month, each biblically named house of faith, after meetings in their respective members’ homes makes a presentation to the church at large, demonstrating a biblical theme or concept. It is from these house meetings that members come to know each other, share prayer requests, and family needs whether in Africa, Latin America or in the United States. For members who have had their prayers answered either by obtaining visas, jobs or promotion, testimonies are given during the worship service to confirm the power of prayer and divine intervention in a seemingly difficult situation.

A Regular Church Service at Hands on Christian Church

The church is currently housed in a rented building belonging to the Catholic Church. Until recently, the worship service has been preceded by Sunday school service at 9 a.m. At 10.30 a.m. the music team leads the congregation in an opening prayer and the director of music starts with songs and choruses familiar to most members of the congregation. Unfamiliar songs are displayed through the use of overhead projector. W.E.B. Du Bois noted that “three things characterized the religion of the Africans brought involuntarily to the United States – “the preacher, the music, and the frenzy.”[7] Having attended not a few black churches myself, both orthodox and the neo-Pentecostal types, one can surmise that the services at Hands On exhibit a more mellowed fashion of the aforementioned characteristics of the black church. However, the senior pastor seems to be uncomfortable with churches that are too “dignified and frozen.” He would often enjoin the church, “your worship and praise to God is more important than my preaching because it is in praises that the door of heaven is open and blessings are released.”

Depending on the types of choruses sung, oftentimes, the congregation marches in circle, dancing on the aisles with vigor in praises and raising of hands to demonstrate and be thankful to the grace of God in going through another week of victory. The praise/worship part of the service goes on until around 11 a.m. or shortly after, then announcements and welcoming of new visitors are made by one of the pastoral team. This is followed by the communion service, which is usually depicted as a moment where not only sins, but also ailments and other needs are healed and met respectively because of the sacrifice of Christ on the cross of Calvary.

The communion is usually followed by pastoral message, usually given by the senior pastor or by a guest speaker. The guest speakers over the last two years have varied from white and black preachers, preachers of Indian (southeast Asia) as well as preachers from Africa, mostly from Ghana, Nigeria and Zimbabwe. There is a particular theme for every month of the year. For example, one month may be “month of good report or month of appreciation, to month of fulfillment or month of great expectation.” Because most members of HOCC are immigrants, problems associated with immigration papers for loved ones overseas and in the United States have sometimes predominated the overall members’ needs of prayers. Others needs include housing, jobs, education, finances and spousal needs for children as well as the main need for the church’s need of relocation into their own building. The last weekend of every month is specifically set aside for “bombarding the kingdom of heaven” for some seemingly insurmountable needs and problems. The last Friday of the month is devoted to all night prayer meetings where interested and needy members congregate in the church for prayer meeting starting at 10 p.m. and going on until 3 a.m. or 5 a.m. These hallowed hours of prayers are seen as the hours of personal or collective break-through.[8]

While the worship service at HOCC can be properly termed Pentecostal in nature, overall, its preaching and biblical orientation are in line with what Geri tar Haar called “the main elements of all black church traditions” which include:

The power in the power of the Spirit, the concept of a church as constituted by the community of believers, the importance of worship as a form of celebration, the central role of the Bible, the emphasis of the concept of love, and the meaning, which they ascribe to healing.[9]

The centrality of the scripture cannot be overstated in pastoral sermons and admonitions. This is notwithstanding whether the speaker is the senior pastor himself or a guest speaker from inside or outside the United States. Again, the words of Du Bois concerning the role of the preacher in the Black Church is very instructive here. Describing the scene when he first visited a black church in the South, Du Bois asserted, The centrality of the scripture cannot be overstated in pastoral sermons and admonitions. This is notwithstanding whether the speaker is the senior pastor himself or a guest speaker from inside or outside the United States. Again, the words of Du Bois concerning the role of the preacher in the Black Church is very instructive here. Describing the scene when he first visited a black church in the South, Du Bois asserted,

A sort of suppressed terror hung in the air and seemed to seize us – a pythian madness, a demoniac possession that lent terrible reality to song and word. The black and massive form of the preacher swayed and quivered as the words crowded to his lips and flew at us in singular eloquence.[10]

While most of the preachers witnessed at HOCC may not be massive in physique, (the senior pastor is certainly of medium build and leanness), however, the conjuring and incantational conviction in the power of the spoken word of God is reminiscent of the functions of the priest, the prophet and people, all congealed at one hallowed moment of the service. The pastor epitomizes the functions of the priest and the prophet by utterances and prophetic declarations and the peoples’ echoes of “Amen” in affirmation to his utterances are part of the regular characteristics of the worship service.

Most frequently, the senior pastor would utter positive words of confession and the congregation would similarly respond: “I am a champion, God is not finished with me yet, no matter what I am going through in this foreign land, I am more than conqueror. In my visa application, in my job, in my education, among folk in Africa, I am a champion.” He would then allude to what it takes to be a champion in the physical sense, by stating that a champion is one who has denied himself/herself of what it takes to win the championship title. In essence, because the champion is focused and purposeful, s/he does not let down his/her guard even in the midst of the stresses and strains of life. This admonition with relevant and appropriate biblical and African oriented stories of victory has often serve as a bulwark against whatever opposition or problems members may be going through.

On one occasion, he enjoined members to “fly higher” in the midst of the post 9/11 trauma on foreigners in the United States. The senior pastor once to a story about gathering of the birds in a particular village in Africa (orthodontic gathering), where one of the birds asked a particular bird why it has chosen to fly higher than usual. The bird responded: “I am flying higher because men of today have learned to shoot without missing.” The pastor would then challenge the church to seek to fly higher despite the overall intensity of anti-foreign sentiments especially on members of Muslim extraction.[11]

The pastoral message is not restricted or limited to spiritual things alone, but specific recognition is given to a particular country that constitute the overall make up of Hands On Christian Church. On a monthly basis, the geographical location, people, religion, politics, ethnicity of that particular country is briefly given to the church at large for further information and education so that involvement and prayer for such country will be more meaningful and focused. In recent weeks, Liberia has been the focus of prayer and informational focus. The pastoral message is not restricted or limited to spiritual things alone, but specific recognition is given to a particular country that constitute the overall make up of Hands On Christian Church. On a monthly basis, the geographical location, people, religion, politics, ethnicity of that particular country is briefly given to the church at large for further information and education so that involvement and prayer for such country will be more meaningful and focused. In recent weeks, Liberia has been the focus of prayer and informational focus.

Other Functional Roles of the Christian Faith Among African Immigrants

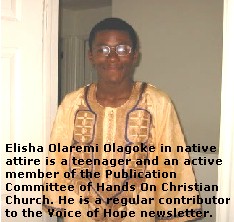

From church pronouncements, pastoral sermons and admonitions, church newsletters,[12] Hands On Christian Church sees itself as an international, intercultural, interracial immigrant church with specific roles and functions. The church does not see emigration to West as the be all and end all, but as part of a divine call whereby the oppressed and the downtrodden of the world are divinely called to mission to speak to the cultured despisers of the faith in the West. This is reminiscent of the biblical valley of dry bones in the book of Ezekiel. The pastor and many members have lived in other parts of the world including Europe and are apt to see the religious landscape in the West as a “valley of dry bones.” The clarion call to speak life to the dry bones becomes part of the mission objectives of the church.

In October 2002, one guest speaker from Africa once alluded to the members’ presence in the West by stating: “if the history of your country, or your host country or your family remains the same while you are still alive here in the West, you have become irrelevant and it is better you are not part of that history.” In essence, emigrating to the United States to escape the social, political and economic debacles is not enough if one has not aligned oneself to the program of God in this day and age. The upshot is to make a difference in other peoples’ lives based on the difference that Jesus of Nazareth has made in one’s life. This is the crux of human existence and it is the primary rationale for God allowing them to eat at the banquet table of the West when thousands in the motherland have sought fruitlessly to obtain visa to emigrate. There are other roles that the church performs for its members as they transit to the civic life in the United States.

Ethnic Identity Formation at Hands On Christian Church

Apart from cell group meetings in various houses, other aspects reinforcing identity formation at Hands On Christian church include cultural continuity through, dress, food, language and music. Each of these aspects plays a significant part in cultural continuity, adaptation, and transition to a newly adopted homeland.

Dress as a Method of Cultural Continuity/Ethnic Identity

Three-quarters of Africans coming to Hands On Christian church every Sunday wear their traditional African dresses. Men wear Dashiki, Agbada, Dandogo, and Buba while women – Gele, Iborun, and Iro ati Buba with designs that are sometimes hand sewn. Most of these clothes are made from cotton materials or other light materials so that even a two-piece or three-piece attire does not adequately provide enough warmth especially during the cold weather. Nevertheless, members gladly wear them as part of cultural rememberance of where they come from and well as passing on their traditional dress codes to the coming generations.

It is not unusual for children to be dressed in attire similar to their parents. Asked why this continuity is important, most members stated that “this is part of our culture and we must not allow it to die down in a foreign land.” Some said that wearing home made clothes gives them a sense of pride, a sense that they belong and a sense of continuity of African identity in a place where cultural values from the continent are often relegated to the background or flagrantly denigrated.

On one occasion, the pastor lamented on the marginalization of Africa and Africans. He drew inspiration from a story in the bible where the disciples of Jesus questioned each other about the geographic area in Israel where the Messiah would come from. One of the disciples, Nathaniel, on hearing that the Savior of the world is from the city of Nazareth asked, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” The pastor lamented that the media and people often ask the same kind of question about Africa. The response of one of Jesus’ disciple to others to “come and see” this same Jesus who had come out of Nazareth is the same response the pastor often encourages members to use in answering negative stereotypical images about Africa. The pastor constantly exhorts that through members’ lives of commitment, character and civic responsibilities, they should draw people ignorant of Africa to the values and principles that traditional Africa inculcates. The Africa of CNN, he asserts, is vastly different from the Africa he knows and where he grew up. The congregational response to his statement is usually affirmative.

Elaborating on invidious stereotypes and stigmatization, the pastor often alludes to the various forms degradation he has suffered in airports where his luggage and passport were closely scrutinized because most airports do not look kindly at Nigerians. “A few bad eggs in the country do not justify the belief that all Nigerians are bad.” He asked rhetorically: “The fact that some Americans are drug dealers does not make every American a drug dealer.”

Wearing one’s national dress, therefore, serves as a source of pride and celebration of the culture where one comes from no matter if it is being denigrated by the world at large. On special occasions, the pastor and his wife also adorned themselves in traditional Yoruba attire. He encourages Spanish-speaking people in the church to do likewise and to let the church know when specific holidays like independence day or festival days are being celebrated in their respective countries. The traditional dresses are also ways of encouraging new members to come to the church.

The fascination with exotic things from Africa attracts the attention of new comers, some of whom visit the church out of curiosity. Often such people are impressed and decide to join the church. A typical example is an American interracial couple who moved to Denver from Michigan and who are now active members of the church with ministries in the areas of prisoner’s rehabilitation and children education. In fact, the husband recently returned from a four-week visit in Africa very impressed, that he and his family sometimes come to church adorned in traditional African attire. This particular trip was under the auspices of the pastor’s overall goal of bridging the gap between Africans and African Americans.

A few members have their own stores in the Denver metro area where they sell African goods so that African clothes do not necessarily have to be brought to the United States from the continent. Furthermore, stores in Denver and Aurora offer African attire while a few women in the church specialized in the art of making the traditional outfits. They often work from their homes and charge minimally for making these dresses.

Food as a Method of Cultural Continuity

Whether it is birthday celebrations, wedding anniversary, cell groups, cultural celebration and home visits, African foods are served liberally by the host. Ancient biblical and traditional African practices are often invoked to underline the significance of food in human interaction. While encouraging members to visit one another and be open to others from a different cultural tradition, the pastor often alludes to places where Jesus met people as usually saturated with food. Biblical examples where gatherings revolve around food include the wedding at Canan, the visit to Peter’s house, the visit to Mary and Martha’s house, the last supper, and when Jesus resurrected and gathered the disciples around a breakfast meal of fish.

In the African tradition, food also takes on a very important role in gatherings – from the womb to the tomb. During birthday celebrations, marriage, business success, house warming, purchase of a new car, invitations to friends to share in one’s promotion, and even in death, parties and food consumption can last for days. In some African cultures, like the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria, it would be offensive to visit somebody’s house and refuse to eat what was hospitably offered.

Tedros Kiros examines the traditional African approach to food in the community as an inalienable right as opposed to the modern view, which treats food as a commodity. Most members of the Hands On Christian church hold a traditional African worldview, a perspective that emerges from having lived on the farm and seldom having to buy food since most food items are grown for consumption. Kiros’ description of the two worldviews suggests that certain aspects of traditional worldviews also have Christian underpinnings. He writes,

There was a period in the history of Africa prior to its penetration by colonialism and by the global world economy during which African food producers circulated and consumed food among themselves. The tendency to look at food as a commodity, accessible only to those who have the means to buy food, thereby securing an everyday existence, and to look at those who fail to have the means as predestined victims of poverty famines, starvation, and malnutrition has become almost second nature in the modern age.[13]

Two points need to be made here. First, during my interviews, some African immigrants expressed amazement at the abundance of food supply in the United States where it is estimated that less than two percent of the population are farmers and yet, they provide enough food for a population of over 240 million. Respondents also recognized that despite this country’s material prosperity, food, shelter and the pursuit of happiness are hard to come by for those who are hard-pressed financially.

The commodification of food in the modern economies often makes these immigrants long for the “good old days” in African villages where oranges, mango, banana and apples were seldom placed in the market for purchase. It is in this light that food becomes an essential part of fellowship for these immigrants. They reminisce about the traditional landscape where they come from and where in times past commodification of food was not as intense as it is now. In these house gatherings and some church events, so much food is provided that the unmarried members are encouraged to take food home.

I remember a gathering in one of the cultural groups where an amazing amount of African food was provided. I asked the host if his wife had spent an entire week preparing the food for the fifty church members who came to visit the member. He responded that women of the church join together at such times to prepare food and make sure that more than enough is provided. Here is an instance where the concept of African hospitality and reception is practically manifest. The interaction and the fellowship engendered under such auspices provide a basis for positive transition into the civic life of the United States.

When members contrast the abundance of food in the United States to famines in Ethiopia and Somalia, they often invoke moral lessons of the traditional African worldview through stories. Most members express the view that even underdeveloped Africa can contribute to Western values, especially in areas of that are not measured in terms of economic or material quantification. Again, Kidros statement in this regard is instructive:

In the traditional African life-world technocratic backwardness and the resistance to modernization is balanced by moral richness and charity. Modernity needs to revitalize the moral richness of the prereflective stages of the life-world. Whereas the African peasant’s resistance to science as a whole may be criticized, his moral sentiments are admirable, so admirable that they can serve as the foundation of African philosophy.[14]

During church gatherings when food is served, prayers are made for those who cannot afford to eat. In addition, concrete measures are undertaken to insure that jobless members are provided for, measures that are reminiscent of the traditional African milieu. Gatherings around food create fun and fellowship and such gatherings also engender other forms of con-associational life-world. For example, it is during these gatherings that the names of volunteers for the next meetings are announced. Such volunteers are then responsible for the physical, spiritual and material needs necessary for the gathering.

Secondly, it is also a time when the African concept of collective Harambe is implemented. The Swahili word “Harambe” has a Yoruba equivalent “Ajo.” “Harambe” concept encourages six or eight-person group members to raise five hundred to a thousand dollars a month or whatever amount are agreed upon. One person in the group is then given the money to start a business venture or to send home to start building a house or fulfill other family responsibilities. Each participant takes turn in contributing and collecting at the end of the month until all participants have collected their own share of the sum of money. Members who have participated in “Harambe” say that this form of enterprise has enabled them to do concrete things that would have been impossible otherwise. Such concept is derived from traditional African economics, which helps the less privileged to fulfill their dreams in business or educating their young ones. It also encourages thrift and saving in easing the transition process to a new culture.

Women's Role in the Reproduction/Formation of Identity Women's Role in the Reproduction/Formation of Identity

Another group in the church that serves as a primary agent for the reproduction of cultural identity and Christian fellowship through food production and preparation is the women’s group. Most members of the church acknowledged the significance which “gathering at the table” plays in their lives at home and among friends. In underscoring the significant role of women in the home or at the church, one woman member said: “Women are the pillars of the home and the church, men are just like caterpillars.” This literally means that women are largely builders of the home and men can often be destroyers as it is demonstrated in the functional role of a caterpillar or bulldozer. Sometimes the discussion in the women’s group revolves around the political implication of wars and chaos that have arisen when men have been national leaders and are bent on plunging the nation into war just to illustrate their masculinity. The destructive result of such actions cannot be over-estimated as evident in the number of orphans, widows and homeless in African countries devastated by wars, ethnic and religious strife.

Women have been seen to play a crucial role in this form of cultural continuity at Hands On Christian Church especially when they engage in the production and preparation of food for the church. Peter Goldsmith underscored the central significance of food and the role of women in sustaining ethno-religious identity and community.[15] Eating together, he argues, creates a sense of community and the process of food preparation itself fosters a sense of identity in a religious context. Food preparation becomes a “ministry” in the service of others and is often seen as a demonstration of one’s God given talent. Most of the foods served in gatherings at Hands On Christian church are ethnic foods, and because the women shop together for the various ingredients, they regard this as a time of fellowship and problem solving period as well as a time of instruction of children and other members of the church. Underscoring the importance of women in food preparation, ethnic reproduction, and identity formation, Helen Ebaugh writes:

Along with participating in the ethno-religious education of children, women’s most ubiquitous role within their congregations are that of ethnic food provider. Whether for formal, congregation-wide social events, less formal religious meetings, or family centered but religiously oriented practices, ethnic food consumption marks the most gatherings of fellow ethnic congregational members. Along with the use of native tongue, the collective consumption of traditional foods constitute what are undoubtedly the most significant ways by which members of ethnic groups define cultural boundaries and reproduce ethnic identities.[16]

Women’s roles at Hands On are not restricted mainly to production and preparation of foods, they also engage in teaching ministry and other services. For example, the senior pastor’s wife is actively involved in preaching and teaching ministry in the church apart from being the leader of the Women’s group. Women are also members of the pastoral team and are also involved in key decision making activities in the church.

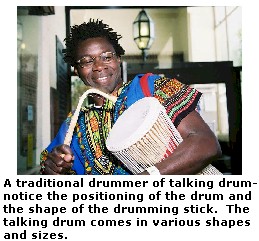

Music is another aspect in the reproduction of ethnic identities or cultural continuity. Special attention will be given to the traditional talking drum, which is one of the ensembles of drum recently introduced by the music department of Hands On Christian Church.

Music and Cultural/Christian Continuity–The Talking Drum

Hands On Christian Church utilizes contemporary Christian music in most of its congregational and choir singing. The “talking drum” is one of the new instruments recently supporting the musical ensembles. The origin of the talking drum, which is a Yoruba musical instrument, is buried in legends and traditions. One legend has it that the wood used in making the talking drum is inhabited by an invisible spirit called “Elegbede,” whose sacred power actually gives talking potency to the drum. Hence the adage, “Gbogbo igi ti Elegbede ba fowo ba, didun ni dun” (all trees touched by the spirit of Elegbede must produce extra sound).[17] The talking drum is vastly different from the drums commonly used in other musical ensembles. When used in performance,

The drum is caught at the left side slightly below the hip level. It is supported by the carrying strap, placed over the left shoulder. The left arm rests over the drum at the center. The left thumb is inserted between the tensioning thongs about two-thirds of the way down the side of the drum. Allowing the hand and arm to “hang” downward and relax, the drum may now be said to be in playing position. About 10-17 tensioning thongs fall within the hand between the thumb and the palm. To raise the pitch of the drum, pressure is exerted simultaneously downward on those thongs and inward i.e. (toward the waist of the drum body) on the thongs-lying under the waist. Thus tones are played by exerting heavy pressure directed from the shoulder downward and inward by the hand, wrist and forearm. Low tones are played by completely relaxing the pressure, and midtones by a moderate degree of pressure. Glides and glissandi are accomplished by applying the pressure immediately after the drum is struck.[18]

Its uses, however, are multi-faceted. First, it was a means of communication – religious communication, political communication, and social communication. During the period of slavery, it served to warning signal to adjoining villages of the on-coming onslaught of slave traders. Because it travels through movement of the wind, the sound of the drum is believed to reverberate as far as five miles to warn people of impending doom. It is also a means of education. Most Yoruba proverbs are commonly expressed to the accompaniment of the talking drum to onlookers as well as participants in ceremonies and other events.

So sacred is the function of the talking drum that during periods of ethnic strife among various Yoruba groups, drummers, who lead warriors into battle, cannot be killed or captured as prisoners of war. Discussing the religious and military function of the talking drum, especially the “dundun” variation, Obiremi notes that drummers remind the combatants of the various exploits and victories of their forefathers and therefore embolden them to continue in battle against all opposition. When the battle is fierce and the opposition is strong, the drummers save lives by playing warning tunes so warriors can retreat. The Yoruba rendition says it best: cannot be killed or captured as prisoners of war. Discussing the religious and military function of the talking drum, especially the “dundun” variation, Obiremi notes that drummers remind the combatants of the various exploits and victories of their forefathers and therefore embolden them to continue in battle against all opposition. When the battle is fierce and the opposition is strong, the drummers save lives by playing warning tunes so warriors can retreat. The Yoruba rendition says it best:

Peyinda rin so, eyin o dun mo

Ogun ti le, ogun ti doju ru,

Peyinda rin ‘so, eyin o dun mo.

Turn back and run, there is danger

The war is fierce, the war is rough

Turn back and run, there is danger.

The aesthetic, religious and political uses of the talking drum provide a sort of prolegomena to its significance in the African Christian churches especially the Hands On Christian Church. First, drums, and especially the talking drum, still speak in the African musical landscape today. For the Hands On Christian church, and other churches in Africa, the talking drum decodes cultural and biblical messages in the same way it does when used in traditional functions. Secondly, it is a source of inspiration for those familiar with its origin, history, and traditional usage. As one member put it, “Without the talking drum in the church music, our singing will be synonymous with playing Hamlet without the prince of Denmark.

Concluding Remarks: Religious Critique Among African Immigrants

Not all African immigrants in the United States embrace the Christian faith, even though most have had substantial exposure to the faith through colonial and missionary education. Literature is replete with the complicity of Christianity to slavery and the colonial project. V.Y. Mudimbe, a Zairean intellectual and Professor of Romance Languages and Comparative Literature at Duke University alluded to the “emergence of three complementary hypotheses and actions in the colonial enterprise: the domination of the physical space, the reformation of the natives’ minds, and the integration of local economic histories into the Western perspective.”[19] Educated in the best of French intellectual tradition, and currently an agnostic, Mudimbe stated further, “the fact that I might not believe in God or in some kind of divine spirit has not prevented me from facing with sympathy the complexity of their fate and modalities of their cultural appropriations.”

The intercultural problematic that Mudimbe maintained in the Tales of Faith is not dissimilar to the quandaries experienced by educated Africans. In fact, most Africans do resonate with the regimented academic structures whether they attended British or French institutions. In essence, Mudimbe’s experiences in the Tales of Faith are, for the most part, the experiences of a post-colonial individual. He stated, “For more than seven years, I lived, thought, and dreamed without interruption in French.” Depending on the colonial language or geographical locale, his assertion can be conversely be that of an English, Portuguese or Spanish colonial subject. On one hand, the upsurge of Christianity in the continent and the massive utilization of the faith as a form of cultural defense and cultural transition by Africans in the Diaspora would be seen as new forms of African initiated obscurantism, fundamentalism, and religious irrationalism. Religion is then seen as a vestige of “colonial mentality” that would hopefully wither with better education and exposure. In this regard, the battle line is then drawn between “logocentrism and emotivism.”[20]

On the other hand, other Africans would see the Christian faith as becoming part and parcel of the African landscape. In essence, the argument here is basically that the baby should not be thrown out with the bathwater. The argument goes further that the project of African synthesis, adaptation, and renovation of the Christian faith to fit the specific African milieu, whether in Africa, Europe or the United States is not just restricted to Africans, but to other cultures as well. The Ghanaian philosopher, Kwasi Wiredu, once observed in a lecture that “no civilization ever existed without borrowing. For Africa and Africans to utilize Christianity or any form of discourse in confronting personal, existential or national issues that eventually brings positive results should be seen as mutually beneficial.

Lamin Sanneh’s frontal critique of religion and culture controversy as well as the significant place of translation of scripture in native tongues is instructive whether one addresses the rapid growth of the Christian faith in Africa or among Diaporic Africans. His argument is worth quoting at length:

… the mother tongue projects of scriptural translation encouraged local people to embrace the new religion while also embracing their own cultures. It seems to be the case that the assurances that converts received from mother tongue literacy introduced fundamental qualification into the schemes of Western cultural and intellectual domination and the forced sequestration of local populations.[21]

The use of the Christian religion as an adaptive mechanism by members of Hands On Christian Church in their transition to the civic life in the United States through the adoption of ethnic, cultural and linguistic forms profoundly illustrates the points underscored by Samin Lanneh. Through the faith, they embrace and engage in the spiritual and cultural processes of “remembering and forgetting” (West, 1993, 1999, Benjamin 1981). Africans, in this regard are apt to remember the goodness of God in their migration pilgrimage in the West. At the same time, they commemorate through celebrations, services, and dedication the remembering and forgetting aspects of immigrants’ experience in their newly adopted country.

African immigrants’ status and plight in the United States can also be understood in the light of the Jewish experience of suffering, especially redemptive suffering in Christ and the prophetic pronouncements that suffering or evil does not have the last word. Scriptural references that are replete with the concept of the goodness of God are often appealed to whether in cases of those looking for visas for their loved ones, naturalization process, job seeking or some of the existential angst associated with living in a foreign culture. The communal gathering of Africans in Hands On Christian Church affirms the primacy of the Christian faith in their transition to the civic life in the United States. It is also a testimony to the mosaic of religious and ethnic diversity in their adopted homeland, the United States of America.

Footnotes

[1]Lamin Sanneh, 1993. Encountering the West: Christianity and the Global Cultural Process: The African Dimension: New York: Orbis Books. I also acknowledge my plurality of cultural indebtedness – educated under several cultural traditions: African, (African traditional religion); Islamic, (Islamic High School - five years); Christian (Attended five different theological schools/colleges, and the modern West (I have lived and attended colleges in both Europe and the United States over the last two decades). return to text

[2]Jurgen Habermas, Religion and Rationality: Essay on Reason, God, and Modernity, Cambridge: The MIT Press, page 1. return to text

[3]As one of the pioneering members of the Fellowship, I was the secretary to the African Christian Fellowship at Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma in the mid-eighties. In recent years, however, increasing number of African immigrant churches have sprung up across the United States. return to text

[4]According to the Denver Post (June 23, 2002), “social workers put the population of Africans in the Denver Area at more than 12,000, allowing for an aversion to filling out forms.” return to text

[5]The paradox of the debate on the secularization thesis becomes apparent here. On one hand these immigrants live in a Western society where religion has undergone mutation or secularized. Peter Berger’s shift in the secularization theory is especially noted in “Epistemological Modesty: An interview with Peter Berger in Christian Century 114: 972-875. On the other hand, Steve Bruce asserted, “only where people still possess a religious world-view are they likely to respond to social dislocation by seeking and being attracted to religious remedies.” See Steve Bruce, Religion in the Modern World, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996: page 125. return to text

[6]Chapter Seven of my dissertation deals with the convergences and divergences of experience between Africans and African Americans. (See Abolade Ezekiel Olagoke, Pan Africanism and the New Diaspora: African Christians in the United States, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Denver Joint Program, August 2002). return to text

[7]W.E.B. Du Bois, The Black Church in America (ed. Hart M. Nelsen et al.), New York: Basic Books, 1971, page 30. return to text

[8]For most members from Africa, all night prayer meeting is not a new phenomenon as this was the practice in most of their churches in their respective countries before coming to the United States. return to text

[9]Geri ter Haar, Halfway to Paradise: African Christians in Europe, Cardiff Academic Press, 1998, page 7. return to text

[10]W. E.B. Du Bois, page 30. return to text

[11]Some members of the church were particularly impacted by the anti-foreign sentiments after 9/11. One Muslim member once mentioned to me that “this is not the time to be a Muslim in America; when people ask for my name now, I usually respond “Ed” instead of Mohammed.” return to text

[12]The church’s newsletter, “Voice of Hope” was inaugurated in January of 2002. return to text

[13]Tedros Kiros, Moral Philosophy and Development: The Human Condition in Africa, Ohio University Monographs in International Studies, Africa Series, No. 61, page xv. return to text

[14]ibid, page 175. return to text

[15]Peter, Goldsmith, When I Rise Cryin’ Holy: African-American Denominationalism on the Georgia Coast, New York: AMS Press, 1989. return to text

[16]Helen Rose Ebaugh and Janet Salzman Chafetz (eds.), Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant congregations, (New York: Alta Mira Press, 2001), page 399. return to text

[17]Michael Ayodele Obiremi, Yoruba Talking Drum: Functions and Aesthetics, M. A. Thesis, July 1991, University of Ilorin, Nigeria return to text

[18]D.L. Thieme, “A Descriptive Catalogue of Yoruba Musical Instruments,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Catholic University of America, 1969, pages 20-21. return to text

[19]V.Y. Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988, page 2. return to text

[20]D.A. Masolo, African Philosophy in Search of Identity, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. return to text

[21]Lamin Sanneh, Encountering the West: Christianity and the Global Cultural Process: The African Dimension, New York: Orbis Books, 1993, page 16. return to text

References

Appiah, Kwame Anthony, 1992. In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pryce, Ken, Endless Pressure: A Study of West Indian Life-Styles in Bristol, Penguin Books: Middlesex, England, 1979.

Browning Don, S. and Fiorenza Francis, 1992. Habermas, Modernity and Public Theology, New York: Crossroad.

Coleman, Simon, 2000. The Globalization of Charismatic Christianity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Colombo, J.A., 1990. An Essay on Theology and History: Studies in Pannenberg, Metz, and the Frankfurt School, Atlanta: Scholars Press.

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1903. The Negro Church: Report of a Social Study made under the direction of Atlanta University: together with the Proceedings of the Eighth Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, held at Atlanta University, May 26th, 1903.

Ebaugh, Helen Rose and Chafetz, Janet Saltzman, 2000. Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant Congregations, New York: Alta Mira Press.

Haar, ter Gerrie, 1998, Halfway to Paradise: African Christians in Europe, Cardiff Academic Press.

_____________, 1992, Spirit of Africa: The Healing Ministry of Archbishop Milingo of Zambia, London: Hurst & Company.

Haynes, Jeff, ed. 1998. Religion, Globalization and Political Culture in the Third World, London: Macmillan Press.

Held, David, ed. 1991. Political Theory Today, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hoogvelt, Ankie, 1997. Globalization and the Postcolonial World: The New Political Economy of Development, Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Hopkins, Dwight et.al. 2001. Religions/Globalizations: Theories and Cases, Durham: Duke University Press.

Kiely, Ray, ed. 1998. Globalization and the Third World, London: Routledge.

Mudimbe, V.Y. 1994. The Idea of Africa, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

____________, 1988. The Invention of Africa, Bloomington: Indiana University Press

____________, 1997. Tales of Faith, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

____________. 1997. Nations, Identities, Cultures, Durham: Duke University Press.

Olagoke, Abolade Ezekiel, 2002. Pan Africanism and the New Diaspora: African Christians in the United States, Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Denver/Iliff School of Theology, August 2002.

Masolo, D.A. 1994. African Philosophy in Search of Identity: Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sanneh, Lamin, 1983. West African Christianity: The Religious Impact, New York: Orbis Books.

____________, 1993. Encountering the West: Christianity and the Global Cultural Process: The African Dimension, New York: Orbis Books.

____________,Stark, Rodney, 2003. For the Glory of God: How Monotheism led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts and the end of Slavery, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

West, Cornel, 1999. The Cornel West Reader, New York: Basic Civitas Books.

___________, 1993. Race Matters, New York:

|